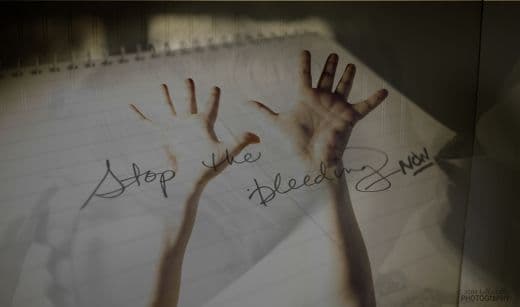

Every year millions of kids deliberately cut their own skin, desperately looking for relief from overwhelming stress, anxiety and insecurity. Learn what’s behind the self-injury problem and how parents can stop the pain.

Caia Pattynama hesitated the first time the scissors pierced her arm. “It really hurt,” she says, “but I figured if I could tough it out, it would prove I could get through the other things happening in my life.” In the seconds it took for drops of blood to appear, Caia, then 15, felt an odd sense of peace. “I knew it didn’t make sense, yet I felt better,” she says three years later. “For that moment, I was in charge.”

Life started slipping out of Caia’s control when her beloved stepfather, Daryl Simpson, passed away unexpectedly. She was just a few months shy of her 14th birthday. Though everyone in the Centennial, Colorado, family–mom Monica Simpson, older brother Jared Pattynama, then 16, and younger sister Kendall Pattynama, then 12–was reeling from the loss, Caia was having a particularly hard time. “She was angry and becoming increasingly withdrawn,” Monica recalls.

Caia started high school in the fall, and Monica hoped her daughter’s mood would improve once the stress of that transition passed. But Caia, a self-described introvert, struggled to fit in. When she did make friends, she was surprised to discover that several of them were into cutting. They said it was calming–which was all Caia needed to hear. In October she started scratching thin lines into her arms with scissors, safety pins and thumbtacks. Soon she was slashing the skin on her arms, belly and legs with whatever sharp instrument was handy. “Sometimes,” she says, “the only thing that got me through the day was thinking about being able to cut when I got home.”

Deflection Game

Caia’s story isn’t unusual–a third to half of kids ages 12 to 18 engage in self-injury at least once, according to a Psychiatry study. Actions include cutting, scratching, burning, repeatedly biting or picking at skin, or embedding small objects, such as paper clips or small rocks. Males also punch objects or themselves, or bang their heads against surfaces.

Destructive as this is, most kids–about 60%–aren’t trying to end their lives, which is why mental health experts call it non-suicidal self-injury, or NSSI. “Most want to kill their emotional angst,” says Janis Whitlock, PhD, director of Cornell University’s Research Program on Self-Injurious Behavior. “It’s not that they actually want to die.”

Experts aren’t sure why the act of inflicting physical pain helps, but self-injurers claim they feel more relaxed afterward, apparently exchanging inner angst for the strong physical sensation. Others, emotionally frozen, may want to prove they’re capable of experiencing anything at all. Brain chemistry also plays a role–cutting releases endorphins, resulting in a pleasurable or numbing sensation. “Self-injury is a form of self-medication,” says Whitlock. Though professionals fall short of calling the behavior a true addiction, it can be compulsive: The more a person cuts, the more she’ll crave this relief when tension builds. Over time, the urge becomes impossible to resist.

As the fall progressed, Caia’s sadness deepened. “Not only had Daryl died,” says Monica, “but Kendall was less available, Jared was living with his father, and I started a full-time job. Everything in her life was pretty much turned upside down.” Monica didn’t know how upset Caia was, however, until she saw cuts on her daughter’s arms. Caia convinced her mother it was a one-time thing, but Monica soon caught glimpses of fresh wounds. Concealing sharp objects didn’t help. “She shaves her legs. She’s got thumbtacks holding up pictures. I couldn’t hide everything.” In December, Monica took her daughter to the family doctor, who diagnosed depression, prescribed medication and suggested a therapist.

Antidepressants or anti-anxiety drugs like serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly given to self-injurers. Unfortunately, in a small percentage of children, SSRIs may induce suicidal behavior (the FDA now requires a label warning). One night Caia told her mom: “If you leave me alone long enough, I’ll do whatever I can to kill myself.” Monica called 911 and Caia was taken to a psychiatric hospital. Her medication was changed, and she attended daily group counseling sessions. The therapy went nowhere, though. “I faked it,” she says. “I told them what they wanted to hear so I could get out of there.” Released after five days, she cut again. “I was flunking school and alienating my family,” she says. “I felt awful, but I just couldn’t find a way to care.”

Rock Bottom

Two months later, after an argument with her mom over a messy bedroom, Caia grabbed a razor blade and carved grid marks into her arm. The next day Monica pulled Caia out of school–figuring she’d get less of a fight that way–and took her back to the hospital. Within days Caia’s doctors insisted she needed the intensive assistance only a residential center could provide.

Monica launched into a major search for a facility. “I was on the computer all the time,” she says. “I hardly slept.” She finally hired an educational consultant who found Open Sky Wilderness Therapy, a program in Durango, Colorado, where Caia stayed for nine weeks while her mom continued looking for a year-round school. Open Sky wasn’t a boot camp, but it did have a rigorous program integrating hiking and camping with individual and group psychotherapy, meditation and yoga. “Caia loves being outdoors, and this place had a strong focus on introspection and relationship building,” Monica says. “Still, sending her away was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.” Caia loved Open Sky. “It was a slap in the face to be removed from everything that gave me comfort,” she admits. “They take your clothes and issue you new ones. You do laundry with a plunger and bucket and carry a huge backpack. But it was what I needed.”

With Caia gone, Monica toured several year-round facilities and finally chose La Europa Academy, in Salt Lake City, for its focus on fine arts. In addition to therapy, kids at La Europa learn to express themselves through photography, dance and music rather than resort to self-destruction. (They receive school credit, and take academic courses too.)

Caia was away for a total of 13 months, and the reentry was bumpy. “It was hard to transition to my old life,” she says. A few weeks after she got home she cut, then immediately went to her mother to confess. “She was so sad and disappointed in herself,” Monica says. “But I told her one moment doesn’t undo all her hard work.” And, in fact, slipups are common. “Many recovering people test the behavior, and the majority find that it no longer provides relief,” says Wendy Lader, PhD, president of Self Abuse Finally Ends (SAFE). Caia, says her mom, is now part of that group.

With her daughter stable, Monica faced a different challenge: paying the $200,000 tab for Open Sky, travel and the La Europa stay. She emptied her retirement savings and borrowed the rest. Fortunately, most teens don’t require such extensive–or expensive–intervention. “Kids who’ve just started to cut do well with outpatient therapy,” says John Peterson, MD, director of child and adolescent psychiatric services at Denver Health Medical Center. Generally, this means 6 to 12 months of treatment at a cost of about $8,000, some of which may be covered by insurance. (Residential treatment runs about $10,000 to $45,000 monthly.)

Caia is still taking medication and gets overwhelmed and depressed at times, says Monica. “But now on a hard day she comes home and heads straight to the piano to play and blow off steam.” The scars on her arms and legs are forever, but Caia has decided that’s not always so bad. “A girl at school noticed the marks and showed me her fresh cuts,” she says. “I told her I know what it’s like to be sick of it all and just want the pain to stop. I was so thankful I could say there are better ways to deal with those feelings.”

Signs of CuttingSelf-injurers are good at hiding evidence. Look for:

- Mysterious bruises, cuts or wounds.

- Wearing long sleeves, jackets or pants year-round, or using other cover-ups, like wristbands. Disney star Demi Lovato, 18, who admitted last spring to being a cutter, resorted to scar makeup and big bracelets to fool those close to her.

- Unwillingness to participate in activities like swimming that expose skin.

- Spending long periods of time alone, particularly in the bathroom or bedroom.

- Bloodstains on clothing or tissues.

- Razors, knives or other sharp objects hidden among belongings.

- Withdrawal from family or friends.

If You Discover Your Child Is Cutting

- Avoid overreacting or judging. Expressions of shock or horror and statements like “How could you do this?” add stress and discourage your child from confiding in you.

- Seek professional help immediately. The more ingrained the habit, the harder it is to overcome.

- Show respectful curiosity. In a matter-of-fact tone, ask leading questions to help your child acknowledge her problem and recognize she needs help. Try, “How do you feel before and after you cut?” or “What kinds of things make you want to injure yourself?” or “How does cutting help you feel better?”

- Monitor computer usage. There are message boards that encourage self-injury by providing tips for cutting and concealing marks.

- Be observant. Many kids go through cycles of cutting when they’re feeling out of control, then stopping during periods of calm.

- Don’t use punishments (like grounding) or rewards (letting him stay out late). They rarely work. Cutting is a medical issue, not a disciplinary one.

Treatment for Cutting

Not just any therapy will do. Kids who self-injure occasionally stop on their own, but parents shouldn’t count on it. “Cutting is only a symptom,” says Lader. “They won’t get better until they overcome their inability to handle emotions.” And that usually requires professional assistance. The most promising approach so far involves dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which teaches teens two things: how to deal with stress, and how to be more effective in relationships. “The focus is on mindfulness, recognizing and accepting whatever’s coming up at any particular moment,” says Dr. Peterson. “Patients learn to be at peace with negative thoughts and feelings as they arise, rather than do things to try to force them to go away.” Family therapy is also an integral part of recovery. “Teens who feel distant and disconnected at home are much more vulnerable,” says Dr. Peterson. “Kids who are able to decompress by talking to parents are far safer.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

July 2011. Article courtesy Family Circle magazine.

please i hope you can help us. we can not find anyone to help us. we have 2 girls one has been cutting for 3 years and now her sister is starting! they both talk about killing them self and the doctor has heard them. they have even told him. their mom and dad have passed away so they are on medicaid. HELP US

Hi Leeann,

Sorry for the late reply. Are you in Canada or the US?